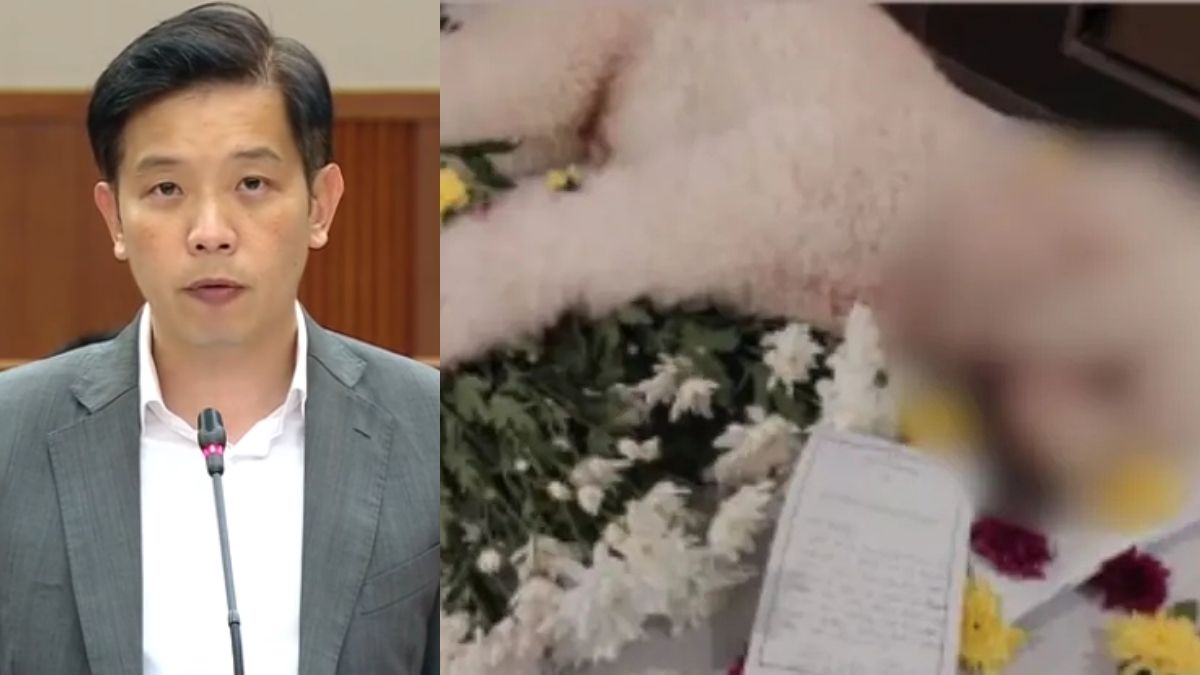

Andre Low calls for evidence-based thresholds and judicial oversight in online harms bill

Workers’ Party NCMP Andre Low has urged amendments to the Online Safety Bill to introduce judicial oversight, protect public interest speech, and ensure decisions are evidence-based. He also requested clarity on how the Bill will be applied in specific scenarios, including doxxing and shadow banning.

- WP NCMP Andre Low supported the intent of OSRA but raised concerns over its current structure and safeguards.

- He proposed amendments to raise the evidence threshold for enforcement, protect legitimate speech, and introduce judicial appeals.

- Low sought clarification from the Government on the Bill’s implications for doxxing, exemptions for public agencies, and content moderation powers.

Parliament began debating the Online Safety (Relief and Accountability) Bill (OSRA) on 5 November 2025, at its Second Reading, following its introduction by the Ministry of Digital Development and Information (MDDI) and the Ministry of Law (MinLaw).

The Bill sets out a legislative framework intended to strengthen protections against online harms and improve access to redress mechanisms for individuals affected by such harms. It supplements existing regulatory and criminal laws by introducing new statutory provisions targeted at harmful online conduct.

Among its key features, the Bill proposes the establishment of a dedicated Online Safety Commission (OSC) to receive and act on victim reports, a set of statutory torts to provide civil remedies, and expanded powers for authorities to request user identity information from digital platforms under defined circumstances. Certain platforms may also be required to take further steps to identify users responsible for online harms.

According to the Government, the Bill is a response to increasing public concern over a range of online harms, including doxxing, cyberbullying, online harassment, the non-consensual distribution of intimate images, and content inciting racial or religious hostility. Surveys cited by MDDI and civil society organisations indicate that many individuals in Singapore report exposure to such content or behaviour, with some experiencing lasting psychological and social impact.

The introduction of statutory torts and broader disclosure obligations has prompted discussion about their potential impact on digital privacy, freedom of expression, and the responsibilities of platform providers. The Government has stated that safeguards will be included to prevent misuse of disclosed information, and that decisions made by the OSC may be subject to appeal.

Safeguards required to ensure fair and accountable enforcement

Speaking during the debate, Workers’ Party Non-Constituency MP Andre Low expressed support for the general intent of the OSRA Bill but raised a series of structural concerns. His speech focused on the Bill’s exercise of state power, the standards of evidence required for action, and the protection of legitimate speech.

Low argued that the current threshold for state enforcement—“reason to suspect”—was too low for the powers being granted. This language, he said, permitted action based on subjective suspicion rather than objective evidence. He proposed raising the threshold to “reasonable grounds to believe,” aligning with standards used in the UK’s Online Safety Act and Canada’s Bill C-63.

“This distinction matters,” he said. “If we are serious about protecting victims, we must be equally serious about ensuring the Commissioner’s enforcement powers rest on evidence, not suspicion.”

Protecting public interest speech and disclosure

Low also highlighted the risk that the Bill, as drafted, could inadvertently penalise legitimate speech. Using examples such as criticism of public officials, victims warning others of harassment, or journalists exposing wrongdoing, he pointed to gaps in Clauses 9, 11, and 19, which define online harms such as harassment and non-consensual disclosure.

To address this, he proposed amendments that would exempt speech or disclosure where the public interest clearly outweighs any harm. These changes are modelled on established defences in common law jurisdictions like the UK and Australia.

“These amendments do not weaken the Bill. They sharpen it,” he said. “They ensure the Commissioner’s powers are used to protect victims, not to chill legitimate speech.”

Judicial appeals and oversight mechanisms

Low's third key amendment proposed establishing a right of appeal to the High Court on specific legal or factual grounds. He criticised the current model, which allows for appeals only to an internal Ministerially-appointed committee, with no further recourse.

“This is not about distrusting the Commissioner or the Minister,” he stated. “It is about institutional design. Independent oversight of executive action is not a burden on the system. It is the system.”

Under his proposed clause, appeals to the courts would be permitted only on defined grounds—such as legal errors, factual disputes over whether harm occurred, or technical infeasibility of compliance. This, he said, balanced judicial oversight with efficiency.

Seeking clarifications on critical provisions

Beyond formal amendments, Low asked the Government to clarify several key provisions in the Bill.

He raised questions about:

-

Doxxing definitions: Whether victims who name their harassers could themselves fall afoul of the law.

-

Standing to appeal: Whether content creators can appeal OSC directions issued to platforms, especially when their content is affected.

-

Prescribed connection to Singapore: How the eligibility criteria would apply to foreign spouses or overseas former residents targeted by Singapore-based actors.

-

Public agency exemptions: Why public agencies are exempt from OSC directions and civil liability, even if their platforms are involved in online harm.

-

Shadow bans and class-of-material directions: How powers to reduce engagement (Clause 40) or block classes of content (Clause 30) would be exercised, and whether users would be notified.

-

Consistency of decisions: Whether OSC decisions would follow precedent or be guided by ministerial clarifications, and whether there would be a public record of enforcement decisions.

Low warned that the power to reduce engagement without notification—a form of shadow banning—risks undermining transparency. “The victim will continue to see the harm, wondering if their report achieved anything at all,” he said.

He also cautioned that class-of-material directions could unintentionally suppress legitimate content, such as that published by victims’ advocacy groups.

Protections must be matched by fairness

Low concluded his speech by reiterating his support for the Bill’s goal of protecting victims of online harm. However, he emphasised that the powers it introduces must be exercised with clear safeguards, institutional checks, and respect for legal norms.

“The Bill’s ambiguities… are not minor,” he said. “They go to the heart of who is protected, who is excluded, and whether this regime operates fairly.”

He urged the Government to accept the proposed amendments, or provide clear answers on how these powers would be applied in practice.