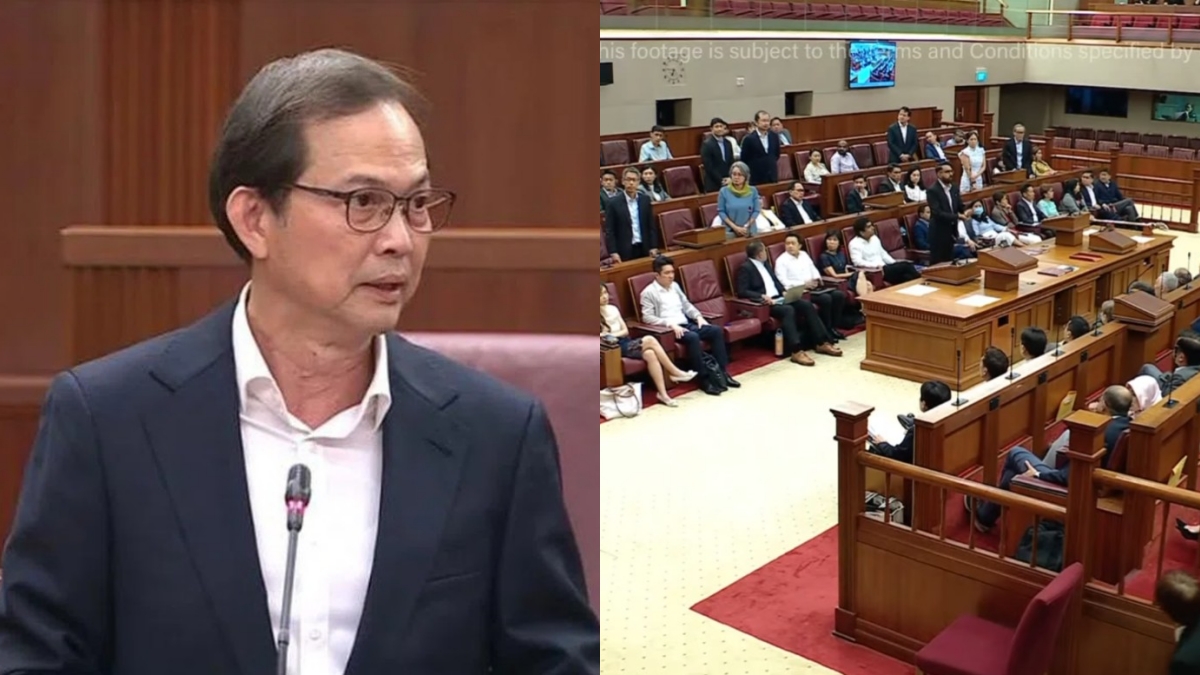

Eric Chua rejects WP’s preschool voucher proposal, warns scheme may raise fees without improving quality

Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Social and Family Development Eric Chua has rejected a Workers’ Party proposal to introduce preschool vouchers, warning that such a scheme could increase fees without improving access or quality. WP’s Kenneth Tiong had argued that vouchers would promote fairness and competition across preschool operators.

- Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Social and Family Development Eric Chua rejected the Workers’ Party’s proposal for a preschool voucher scheme.

- He warned that such a system might raise preschool fees without improving access or quality.

- WP’s Kenneth Tiong argued that vouchers would create fairer competition and greater parental choice.

SINGAPORE: Implementing a preschool voucher scheme could drive up fees without improving accessibility or quality, Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Social and Family Development Eric Chua said during Parliament on 14 October 2025.

He was responding to an adjournment motion by Workers’ Party (WP) Member of Parliament Kenneth Tiong, who had proposed reforms to make Singapore’s preschool education system fairer and more diverse.

WP calls for vouchers to empower parental choice

Tiong, MP for Aljunied GRC, suggested replacing direct operator grants with per-child subsidies issued in the form of preschool vouchers.

These vouchers, he said, would allow parents to choose any licensed preschool — from government-supported centres to private Montessori and faith-based schools.

The WP had earlier included this proposal in its manifesto ahead of the 2025 General Election, arguing that vouchers would promote transparency, diversity, and parental autonomy in early childhood education.

Citing media reports of preschool closures, including the Red SchoolHouse @ Toh Tuck which allegedly failed to pay staff after shutting in May, Tiong said independent operators were being squeezed out.

He noted that Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA)-supported operators and Ministry of Education (MOE) kindergartens enjoyed direct funding, favourable access to sites, and the “full backing of the national budget”.

“Even church kindergartens, who have operated for decades paying zero rent to use church premises, are also shutting down,” he said, adding that their numbers had halved from over 200 to just over 100 in a decade.

Independent operators facing ‘distorted market’

Tiong argued that the system of direct operator subsidies had created a “deeply distorted market” that trapped independent providers.

Subsidies from ECDA and MOE were only available to selected operators, giving them a competitive edge while smaller players struggled with shrinking enrolment and staffing shortages.

“These challenges have forced many independent operators to consolidate, sell, or shut down,” he said.

Under his proposed voucher system, funding would follow the child rather than the operator, ensuring parents could select schools that matched their educational preferences. “It forces all schools, including state-backed giants, to compete fairly on quality, philosophy, and service,” Tiong said.

Chua warns of unintended consequences

Chua, however, cautioned that implementing vouchers alone could backfire, leading to higher fees and worsening inequity. He referred to international examples where similar initiatives were abandoned.

In Hong Kong, a preschool voucher system introduced in 2007 was discontinued after it failed to narrow inequalities. Affluent families used vouchers to fund supplementary enrichment programmes, widening educational gaps.

In the United Kingdom, a nursery voucher programme launched in 1996 was short-lived due to its adverse effects on competition, diversity, and educational outcomes.

Singapore’s current approach emphasises affordability and access

Chua said Singapore had chosen a “comprehensive approach” to preschool affordability that combined fee caps with both universal and means-tested subsidies.

Currently, all Singaporean children receive basic subsidies of up to S$300 (US$231) monthly for full-day childcare, alongside additional means-tested support for eligible households.

“As a result of both fee caps and subsidies, we have effectively reduced out-of-pocket expenses while ensuring access and choice of quality preschools,” Chua said.

He added that by 2026, full-day childcare costs before means-tested subsidies would be comparable to what families pay for primary school and after-school care combined.

Incentives for quality already built into subsidy system

Responding to Tiong’s claim that vouchers would give parents greater autonomy, Chua said existing subsidies already reward preschools based on enrolment numbers, indirectly fostering competition.

“Parents today are discerning when choosing preschools that meet their children’s needs and preferences,” he said. “This has promoted healthy competition and consequent improvements in quality.”

Chua emphasised that nearly nine in ten Singaporean children aged three to six are currently enrolled in preschool, showing strong accessibility across the sector.

Different interpretations of global lessons

While both politicians cited Hong Kong’s experience, they differed on interpretation.

Tiong argued the Hong Kong system’s failure lay in using a flat-rate model rather than targeted funding.

He proposed supplementing vouchers with additional support for low-income families, special-needs students, and teacher wage enhancements.

Chua, however, maintained that even with such adjustments, a voucher-based system risked distorting incentives and creating new inequalities.

He reiterated that Singapore’s balanced approach — combining direct support for operators and targeted subsidies for families — remained the most sustainable model.