MOM to expand affordable care options as demand grows, with focus on migrant domestic workers support care

The Ministry of Manpower said it will continue expanding affordable caregiving options as PAP MP Yeo Wan Ling called for fairer maid levies, better training and healthcare support, and more flexible care models to strengthen Singapore’s growing care economy.

- MOM will continue expanding affordable care options while protecting both employers and migrant domestic workers.

- PAP MP Yeo Wan Ling called for fairer levies, better training and healthcare, and more flexible care arrangements.

- The government cited existing support measures, including higher caregiving grants, enhanced training and broader care models.

SINGAPORE: The Ministry of Manpower (MOM) will continue to expand care options while keeping them affordable and accessible, as demand grows for caregiving that meets increasingly diverse needs.

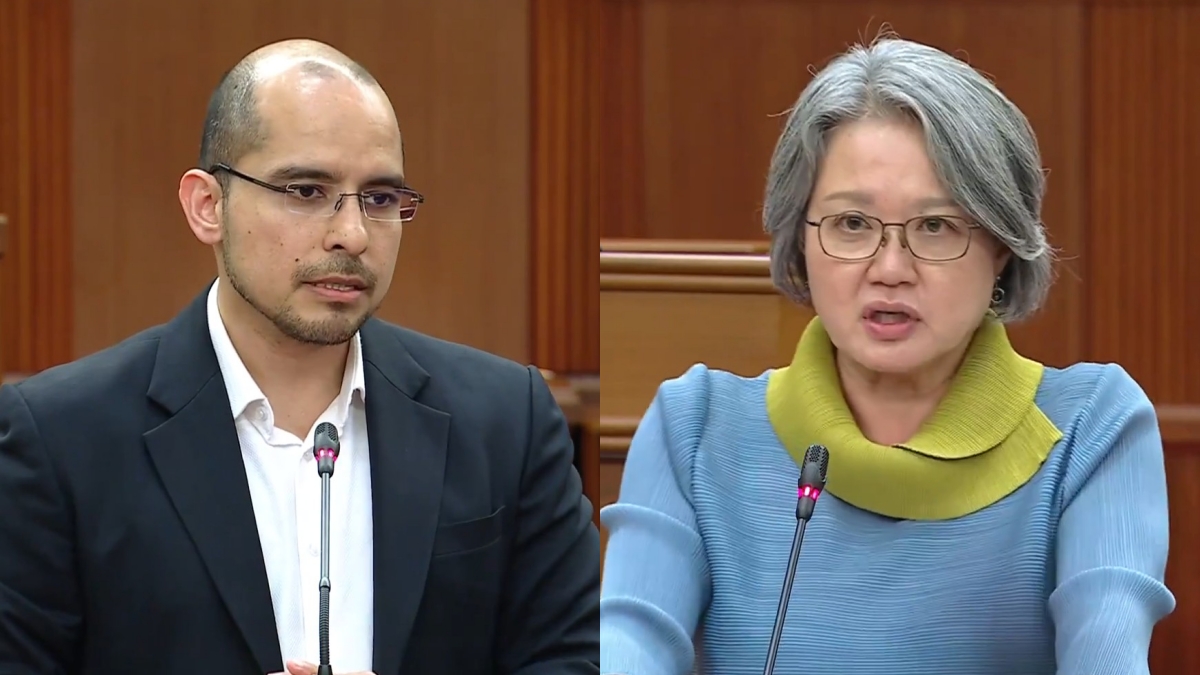

Senior Parliamentary Secretary for Manpower Shawn Huang told Parliament on Tuesday (13 Jan) that a many-hands approach is needed to build an ecosystem of support for migrant domestic workers and their employers.

He added that MOM would continue to safeguard employers’ interests while protecting the wellbeing of domestic workers.

Huang was responding to an adjournment motion filed by PAP MP Yeo Wan Ling, who described migrant domestic workers as a “critical backbone” of Singapore’s care economy.

The motion comes ahead of expanded support for home-based care in 2026, including higher monthly payouts under the Home Caregiving Grant and the island-wide mainstreaming of enhanced home personal care services.

The grant aims to ease caregiving costs, while the personal care services involve trained professionals assisting seniors with daily activities and household tasks.

Migrant domestic workers as a core pillar of care

Yeo, who is also assistant secretary-general of the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC), put forward six proposals to strengthen Singapore’s caregiving landscape by better supporting migrant domestic workers.

These included expanding training to cover dialects and advanced care skills, raising employment agency standards, improving healthcare and mental health support, offering more part-time care options, and introducing a fairer foreign domestic worker levy based on actual care needs rather than age.

“Caregiving is not a single chapter in life. It is a cycle,” Yeo said, noting that Singapore now has more than 300,000 migrant domestic workers, up from about 250,000 five years ago.

“They are not an add-on to our economy. They are the invisible workforce behind our workforce. When they function well, families work. When they fail, families can fall.”

Responding, Huang said migrant domestic workers play an increasingly important role as Singapore faces an ageing population and more dual-income families with limited support from extended relatives.

“Their dedication to caring for the young and elderly in our homes is invaluable to many families in Singapore,” he said.

Affordability concerns and the maid levy

Yeo questioned the current levy framework, noting that while caregiving needs vary widely, levy concessions are largely age-based.

Households currently pay a concessionary levy of S$60 if they have a child under 16, a senior aged over 67, or a person with disability who requires help with at least one activity of daily living. The standard levy is S$300.

“There are gaps in the current levy framework,” she said, urging MOM to review eligibility criteria to reflect “real dependency, not just age”.

She highlighted cases such as early-onset dementia, which may require constant supervision but not physical assistance; frail adults aged 60 to 66; youths above 16 with special needs; and households caring for multiple dependants.

Huang said around 72 per cent of households employing domestic workers already benefit from the levy concession.

He added that individuals who require permanent assistance or supervision for at least one activity of daily living — including those with dementia or special needs — are eligible.

He also pointed to enhancements to the Home Caregiving Grant, which will see monthly payouts rise from S$400 to S$600, alongside a higher per capita household income eligibility threshold from April.

Training for “real caregiving”

Yeo also called for changes to training subsidies to better prepare domestic workers for complex caregiving roles, rather than focusing mainly on household chores.

“Care today is not just about housekeeping. It is about dementia care, post-hospital recovery, disability support, child development and senior wellbeing,” she said.

She urged MOM to expand the Caregivers Training Grant to include advanced home-based care and language training, particularly in Mandarin, Malay, Hokkien, Cantonese and other dialects commonly used by seniors.

In response, Huang said the Caregivers Training Grant was enhanced from S$200 to S$400 per year per care recipient from April 2024.

He added that the Agency for Integrated Care now offers more than 240 courses covering dementia care, eldercare, disability support and post-hospitalisation needs.

Language training, he said, is available through other providers such as NTUC’s Centre for Domestic Employees, the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Cultural Academy, The Salvation Army and other non-profit organisations.

Healthcare protection and flexible care models

Yeo further proposed extending an outpatient primary care scheme to migrant domestic workers, similar to that available to non-domestic migrant workers, to reduce out-of-pocket medical costs.

Currently, domestic workers are not covered by a primary care plan, and mandatory insurance does not include outpatient treatment, which she said could discourage early care-seeking and worsen health outcomes.

She also questioned whether the current S$60,000 annual hospitalisation limit is sufficient for severe medical cases, potentially leaving employers to bear excess costs.

Yeo called for clearer advisories from employment agencies on medical responsibilities and regular reviews of insurance coverage as healthcare costs rise.

Huang said MOM reviews medical insurance requirements regularly, noting that the minimum annual claim limit was raised from S$15,000 to S$60,000 in 2023.

He added that the current coverage accounts for 99 per cent of inpatient and day surgery bills incurred by domestic workers in public healthcare institutions.

Employers seeking greater certainty, he said, can opt for more comprehensive insurance plans that include outpatient care.

Yeo also urged MOM to develop regulated part-time maid and home-care pathways, arguing that live-in domestic workers may not suit every household.

She suggested piloting care-focused extensions under existing schemes, such as part-time carers who are properly trained and fairly contracted, or shared arrangements where multiple families engage a trained worker.

Huang said the government has been working with the caregiving industry to expand both full-time and part-time options.

Under the Household Services Scheme, which allows companies to hire migrant workers for part-time domestic and basic eldercare services, the number of participating companies has grown from about 80 in 2021 to around 240 today.

He also pointed to alternatives such as Shared Stay-in Senior Caregiving, where trained caregivers support groups of seniors living together, as part of broader efforts to diversify care models beyond live-in help.