Shanmugam defends Singapore’s zero-tolerance vaping stance, calls harm reduction “snake oil”

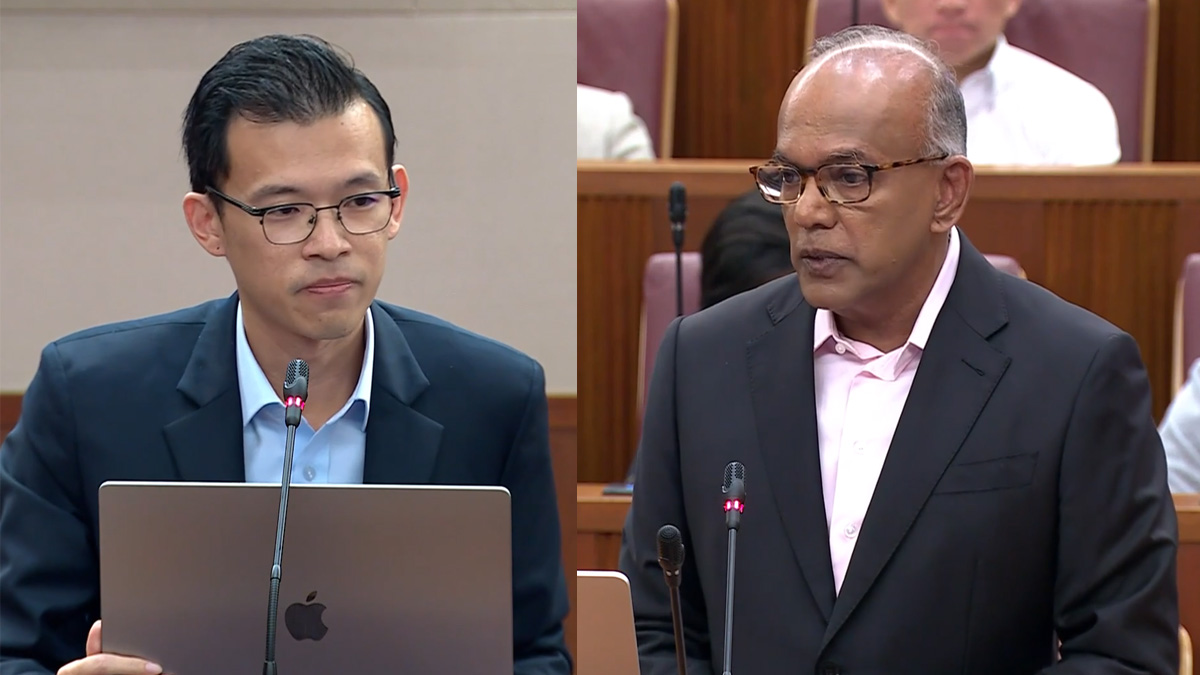

Home Affairs and National Security Minister K. Shanmugam has reaffirmed Singapore’s hardline position on vaping, dismissing harm reduction arguments as “snake oil” and accusing advocacy groups of serving tobacco industry interests. His remarks, made on 30 August 2025, reignited debate over the nation’s strict ban on e-vaporisers.

- Minister K. Shanmugam says harm reduction claims on vaping echo tobacco industry narratives.

- Coalition of Asia Pacific Tobacco Harm Reduction Advocates (Caphra) calls Singapore’s anti-vaping laws “regressive.”

- Experts note that global studies show mixed evidence on vaping’s health risks and role in smoking cessation.

SINGAPORE — Singapore’s firm stance on vaping has come under renewed scrutiny following remarks by Home Affairs and National Security Minister K. Shanmugam on 30 August 2025. Speaking at a grassroots event, he criticised harm reduction arguments and linked pro-vaping advocates to tobacco industry interests.

The comments came in response to a statement issued by the Coalition of Asia Pacific Tobacco Harm Reduction Advocates (Caphra), which labelled Singapore’s anti-vaping policies “regressive” and accused authorities of disregarding scientific evidence in favour of fear-based messaging.

Shanmugam dismissed these arguments as “the same old, tired rhetoric” long used to justify drug legalisation. “They say these electronic smoking devices are a safer alternative… this is a kind of snake oil these organisations peddle,” he said, alleging that groups like Caphra lobby on behalf of Philip Morris International.

Caphra, a New Zealand-based coalition, had earlier criticised Singapore’s intensified enforcement against vaping after several cases emerged of vapes laced with the anaesthetic etomidate. The group warned that criminalising vaping could drive the habit underground, increasing health risks instead of reducing them.

Reinforcing health warnings

Shanmugam’s remarks echoed those made two days earlier by Health Minister Ong Ye Kung, who highlighted that one vape pod can contain as much nicotine as four cigarette packs. Ong said the government’s zero-tolerance policy aimed to protect youth from nicotine addiction and prevent vaping from becoming socially acceptable.

Citing a U.S. study involving 16,000 youths, Shanmugam said those who vaped were three times more likely to become smokers than their non-vaping peers. He argued that the notion of harm reduction was “not suitable for Singapore,” referencing a New York Times report on U.S. cities that reversed pro-vaping policies after observing negative public health outcomes.

The study he referred to was part of a comprehensive umbrella review published in the journal Tobacco Control in August 2025. It analysed 56 systematic reviews covering 384 individual studies and found that youth vaping was consistently associated with increased risks of later cigarette smoking, asthma, and mental health problems.

Researchers identified a “threefold higher likelihood” of smoking initiation among youth who vape as one of the review’s most robust findings.

However, some experts urged caution. Professor Ann McNeill of King’s College London said many included studies were of “low or critically low quality” and warned against drawing strong causal conclusions. She suggested that shared behavioural traits, such as impulsivity, might explain both vaping and smoking uptake.

Singapore’s ban and the harm reduction debate

Singapore banned the sale, possession, and use of e-vaporisers in 2018 under the Tobacco (Control of Advertisements and Sale) Act. Authorities argued that vaping could act as a gateway to smoking, especially among youth, and undermine decades of efforts to de-normalise tobacco use.

The government maintains that its prohibition approach has helped keep nicotine addiction rates among the lowest globally.

However, Singapore’s stance contrasts sharply with public health policy in countries such as the United Kingdom. The 2022 Public Health England (PHE) review, conducted by King’s College London, concluded that vaping—while not risk-free—poses only a “small fraction of the risks of smoking” in the short to medium term.

The review found significantly lower exposure to harmful substances among vapers than smokers, based on biomarkers linked to cancer and cardiovascular disease. It also reported that vaping was the most effective aid for smoking cessation in England, with higher quit success rates when used alongside counselling.

Diverging global approaches

The PHE review highlighted that only 34 per cent of smokers in the UK correctly believed vaping was less harmful than smoking, warning that misinformation could discourage smokers from switching to safer alternatives.

In contrast, Shanmugam cautioned against what he called “being colonised in our minds” by foreign narratives, insisting that Singapore’s success in public safety and health policy justified its zero-tolerance approach.

“Our model works because we don’t compromise,” he said, arguing that allowing vaping under harm reduction frameworks would be equivalent to “giving in to the tobacco lobby.”

Critics call for nuance

Caphra’s executive coordinator Nancy Loucas countered that Singapore’s blanket ban “flies in the face of successful harm reduction strategies that have transformed public health outcomes worldwide.”

She cited the UK’s approach as evidence that regulated nicotine vaping can reduce smoking rates without encouraging new users.

Public health experts note that while nicotine addiction remains a concern, there is an emerging scientific consensus that regulated e-cigarettes are substantially less harmful than combustible tobacco. Studies also show low uptake among never-smokers, suggesting limited gateway effects in populations with strict age and marketing controls.

Despite these global findings, Singapore remains one of the world’s strictest jurisdictions on vaping, with penalties including fines and imprisonment for possession or sale.

Authorities defend this position as a preventive measure, arguing that the country’s success in keeping smoking rates low justifies its uncompromising stance.

Still, critics warn that conflating regulated nicotine vapes with illicit or drug-laced products may obscure important distinctions and hinder evidence-based policymaking.

As the debate continues, Singapore faces mounting international scrutiny over whether its prohibition model protects public health—or risks isolating it from evolving global scientific and regulatory trends.