Hup Chong Yong Tau Foo deeply hurt by STOMP review amid stall’s closure after 40 years

A harsh commentary from STOMP’s assistant editor days before Christmas has left the owners of a long-running Toa Payoh yong tau foo stall devastated. The family-run Hup Chong stall is set to close in January 2026 after 40 years, citing rising costs and shrinking footfall.

- Hup Chong Yong Tau Foo, a long-running hawker stall in Toa Payoh, expressed deep hurt after a critical review by STOMP, published days before Christmas and ahead of its planned closure in January 2026.

- The review, written by assistant editor Cherlynn Ng, criticised the stall's pricing and justification for its closure, prompting public backlash against what many saw as unfair media conduct.

- The stall owners, who had hoped to close their family business quietly after over 40 years, responded emotionally, calling the article shaming and demoralising in its timing and tone.

Hup Chong Yong Tau Foo, a beloved hawker stall in Toa Payoh with a legacy spanning more than four decades, has been thrust into public controversy following a critical review published on 24 December 2025 by citizen journalism platform STOMP.

The stall, which had earlier announced plans to cease operations in January 2026 due to economic pressures, expressed anguish over what it described as a “shaming” piece that dampened the family's final festive season in business.

The article in question, authored by assistant editor Cherlynn Ng, framed the stall’s S$9.20 pricing as excessive and took issue with the reasons given for its closure.

While Ng acknowledged that she had “braced” herself for the cost, she noted that her family and colleagues were “shocked” at the price. She further questioned the stall’s explanation that business had suffered due to nearby competition and work-from-home trends, suggesting instead that the owners lacked “self-reflection.”

This sparked a deeply emotional response from Hup Chong’s proprietors, who issued multiple Facebook posts rebutting the claims.

They clarified that Ng had selected 11 items, of which eight cost S$0.80 and two were priced at S$1 each, with an additional serving of kway teow. The stall typically charges S$1 for noodles, but had waived S$0.20 and offered bean sprouts at no charge. They called her criticism misleading and unfair.

“It turned what should have been a Merry Christmas to the worst Christmas ever in our life,” a post stated, lamenting that the commentary had robbed the family of the quiet dignity with which they hoped to end their chapter in Singapore’s hawker history.

The stall’s current operator, Lu Meiwen, told Shin Min Daily News in an emotional interview that she had broken down in tears after reading the piece. “We were already very sad, and still there are complaints,” she said. “Some people even said they’re glad we’re closing.”

Lu, 41, said her family had served at the location in Block 203 Toa Payoh North for over 10 years, continuing a 40-year legacy that began with her mother, now 80. The matriarch had worked into her seventies and was “shocked and saddened” by the article, according to Lu, who said she regretted even showing it to her.

“She often told me that although she was tired and never became rich, she was proud she could raise her children by continuing our family’s hawker legacy,” the family shared in their Facebook statement.

A stall fighting industry headwinds

Hup Chong’s decision to close was publicly announced in early November. Fourth-generation operator Deng Yongda explained to Shin Min that business had declined by around 20 percent since the pandemic, due to office workers not returning in full force and the opening of competing stalls nearby.

Yet the STOMP article suggested such factors were excuses, stating: “F&B establishments are everywhere in Singapore — you need to give customers a reason to return.”

The stall argued in response that the article disregarded deeper economic and social realities. “Rising operating costs and other realities” were forcing their hand, they said, echoing concerns from many local hawkers about inflation, rental increases, and manpower shortages.

Pricing transparency and hawker economics

A central theme of the dispute was the S$9.20 bill cited in the article. Ng described the price as “not cheap”, saying it felt excessive for a “stuffy coffee shop in the heartlands”.

However, Hup Chong and many supporters pushed back, arguing that the pricing was transparent, with ingredients visibly labelled and self-selected by customers.

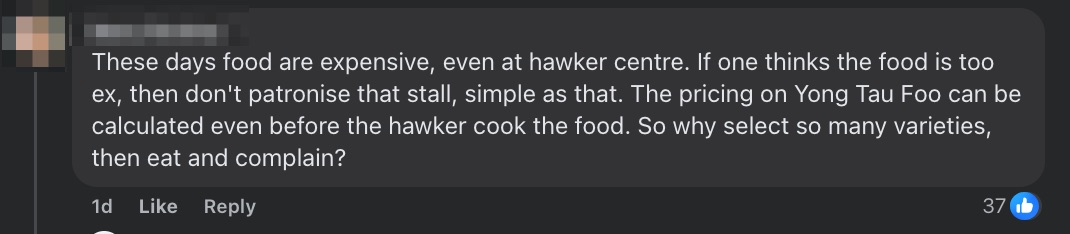

One Facebook user commented: “You pick 11 items and expect it to be cheap? That’s how yong tau foo works. Price is per piece. No one forced you.”

Another wrote: “Try getting that same meal at a food court or mall — it would cost more.”

The stall clarified that a basic meal of five items and noodles costs S$5 — the minimum order. “Is S$5 really so expensive that an editor at STOMP would publicly shame us?” they asked.

Lu also addressed the article’s remarks that some of their ‘premium’ items were processed foods found in household fridges.

She said many items, including those stuffed with seafood and meat, are handmade daily, and that creativity — such as adding cheese to luncheon meat — was aimed at offering variety, not deception.

Public backlash against STOMP and calls for accountability

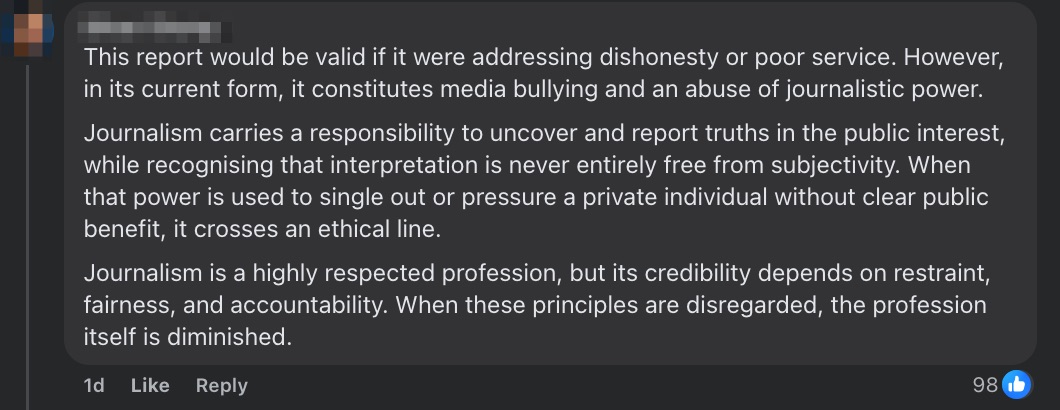

Following the publication of Ng’s article, online commentary flooded in — not only defending Hup Chong but criticising what many saw as journalistic overreach. Readers accused the article of targeting a vulnerable business, with some calling it “media bullying”.

One commenter on Facebook wrote: “This wasn’t investigative journalism — it was a personal rant disguised as reporting.”

Another added: “Even if you didn’t like the food or found it expensive, was it necessary to drag down a stall that’s already shutting down?”

Some pointed out the irony in criticising small hawkers over pricing while accepting inflated costs in cafés or fast-food outlets. Others questioned STOMP’s editorial judgment, especially in publishing such a piece just days before Christmas — a period where most media aim for sensitivity and goodwill.

Cherlynn Ng, the author of the review, was also personally criticised. Screenshots shared on forums alleged that her professional profile had been altered or taken down following the backlash. Some questioned her objectivity, while others demanded an apology or retraction.

Calls for restraint in food journalism were echoed by commenters who said that such writing should aim to explore larger issues, such as structural pressures faced by hawkers, rather than issuing what they saw as moral judgement disguised as opinion.

A bittersweet farewell to a hawker legacy

Despite the fallout, Hup Chong’s owners said they remain grateful to long-time customers who stood by them through the years.

“There are people who can’t wait for us to close,” they wrote. “But there are also those who tell us not to give up. That’s life.”

They ended their Boxing Day post with a message of appreciation: “Your kindness has meant more to us than you may realise.”

The exact closing date has yet to be announced, but Lu and her family hope to wind down operations quietly.

Their story has since become emblematic of the struggles faced by traditional hawkers — and the sometimes harsh scrutiny that even the smallest businesses can endure in the digital age.