Rights group warns of systemic repression in India amid national security escalations

The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) has accused Indian authorities of using national security to justify a crackdown on civil liberties, following mass online censorship and the arrest of an academic critical of Operation Sindoor.

- FORUM-ASIA warns of systemic repression in India, citing censorship and criminalisation of dissent.

- Over 8,000 social media accounts blocked in May 2025, including outlets like BBC Urdu and The Wire.

- Professor Ali Khan Mahmudabad arrested for posts urging peace; later granted bail with speech restrictions.

- Rights groups say India’s use of vague laws undermines academic freedom and press rights.

- Calls made for transparent content regulation and alignment with constitutional and ICCPR obligations.

The Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA) has expressed “grave concern” over what it calls a systemic pattern of repression in India, citing censorship of independent media, curbs on dissent, and criminalisation of peaceful expression.

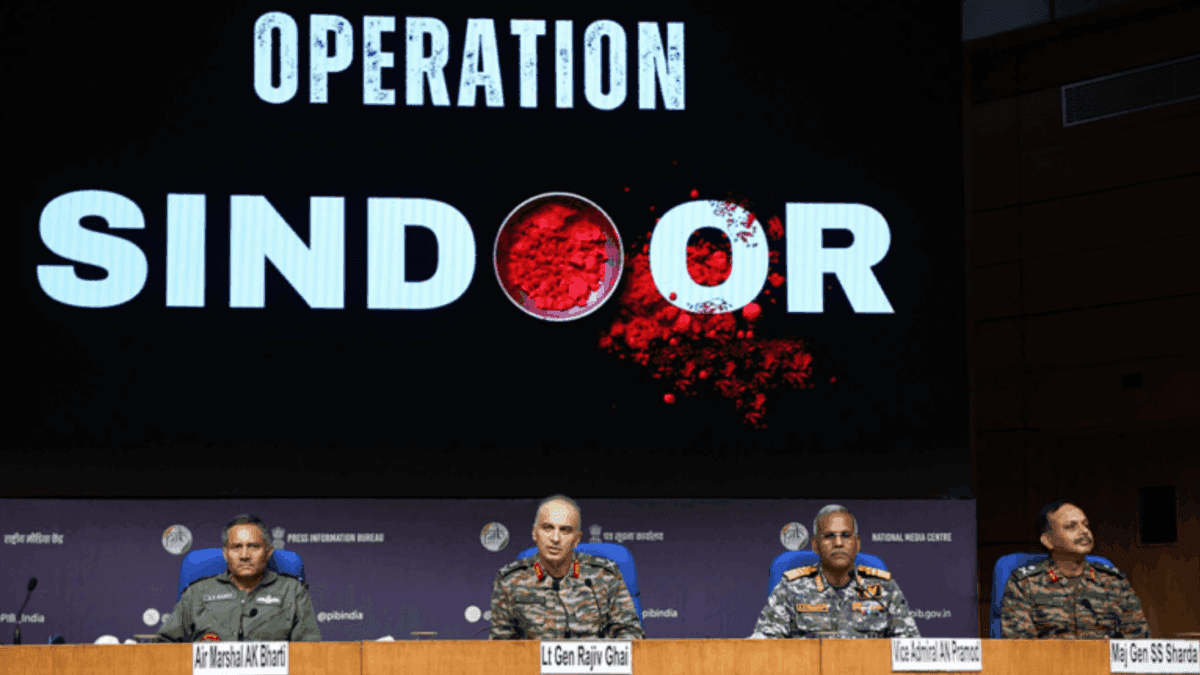

The statement, issued on 27 May 2025 from Bangkok, follows a series of measures taken under the banner of Operation Sindoor—a military strike across the Line of Control in Pakistan-administered Kashmir earlier this month.

According to FORUM-ASIA, India’s response to the operation and its aftermath reveals a broader trend in which national security is invoked to silence critics and restrict freedoms.

“The protection of dissent, academic freedom, and a free press is not optional. It is foundational to the rule of law and a functioning democracy,” said Mary Aileen Diez-Bacalso, the group’s Executive Director.

Online censorship at unprecedented scale

Among the most controversial moves was the blocking of more than 8,000 social media accounts in May 2025, accused of spreading “anti-India” misinformation about Operation Sindoor.

Targets included:

-

Foreign media outlets such as BBC Urdu, China’s Xinhua News Agency, and Turkey’s TRT World.

-

Indian platforms including The Wire, Outlook India, and Maktoob Media.

-

Kashmir-based outlets like Free Press Kashmir and Kashmir Life.

Many takedowns were executed under Section 69A of the Information Technology Act 2000, which allows the government to block content in the interest of national security.

Critics argue that the opaque nature of this process—lacking prior notice, judicial review, or avenues for appeal—erodes public trust and undermines constitutional protections.

FORUM-ASIA noted that such restrictions contravene Article 19 of India’s Constitution and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), both of which guarantee freedom of expression subject only to narrow limitations.

“Freedom of expression is not a threat to national security; it is the bedrock of any functioning democracy,” Bacalso added.

Disproportionate impact on vulnerable groups

Rights advocates stressed that digital censorship disproportionately affects marginalised communities, including Kashmiris, religious minorities, and independent journalists.

FORUM-ASIA argued that the lack of transparency in takedown requests—combined with compliance from global tech companies under government pressure—shrinks civic space both online and offline.

The organisation highlighted the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which require companies to respect rights even under state pressure. In practice, however, affected users often find themselves without remedies or explanations.

Arrest of academic deepens fears

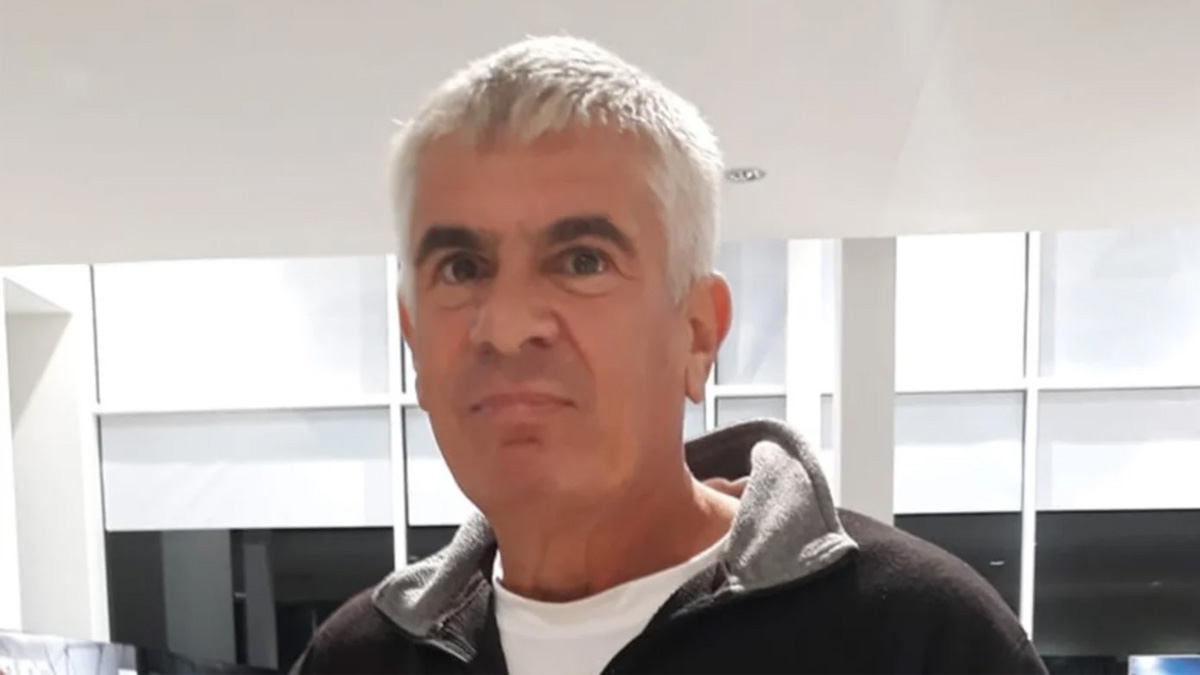

Concerns were further amplified by the arrest of Professor Ali Khan Mahmudabad, a political scientist at Ashoka University, on 18 May 2025.

Mahmudabad was detained in Haryana after posting comments on social media that:

-

Urged de-escalation with Pakistan.

-

Criticised the glorification of war.

-

Condemned online abuse directed at India’s Foreign Secretary, Vikram Misri, who had announced a ceasefire.

Right-wing groups denounced Misri’s actions as weak, and Mahmudabad’s defence of diplomacy was cited in two First Information Reports (FIRs).

He was charged under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), specifically Section 152, which penalises actions “endangering the sovereignty, unity and integrity of India.”

The provision has drawn comparisons to the now-repealed sedition law under Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, widely criticised for suppressing dissent.

Although the Supreme Court granted interim bail on 21 May, it imposed restrictions on Mahmudabad’s speech and ordered a special investigation team to review his posts.

Rights groups warn that this approach risks legitimising state overreach and undermines academic freedom by conflating critical discourse with criminal behaviour.

Legal thresholds and constitutional concerns

FORUM-ASIA emphasised that India’s use of vague and broad criminal provisions—such as those covering enmity promotion or public order disturbance—fails to meet international legal standards of necessity and proportionality.

While Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution guarantees free expression, restrictions under Article 19(2) are narrowly defined.

Current practices, rights groups argue, extend far beyond these limits, effectively weaponising national security laws against peaceful critics.

Call for reform and accountability

The Bangkok-based group urged Indian authorities to:

-

Lift prior restraint orders on online content.

-

End arbitrary censorship and ensure judicial oversight.

-

Develop transparent, accountable mechanisms for digital regulation in line with democratic norms.

It also called for independent review of the Mahmudabad case and other prosecutions under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, to ensure conformity with constitutional and international standards.

“Continued deviation from these principles undermines democratic legitimacy, the rule of law, and public confidence in the justice system,” FORUM-ASIA warned.

Broader context: civic space under pressure

India has long been hailed as the world’s largest democracy, but rights monitors say civic freedoms have come under increasing strain in recent years.

In its 2024 Freedom in the World report, Freedom House downgraded India’s rating due to concerns about political rights, internet shutdowns, and pressure on journalists.

Similarly, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has ranked India low in its World Press Freedom Index, citing harassment of independent reporters and opaque regulation of digital media.

Operation Sindoor and its aftermath, critics argue, reflect a continuing securitisation of governance, where national security imperatives consistently outweigh civil liberties.