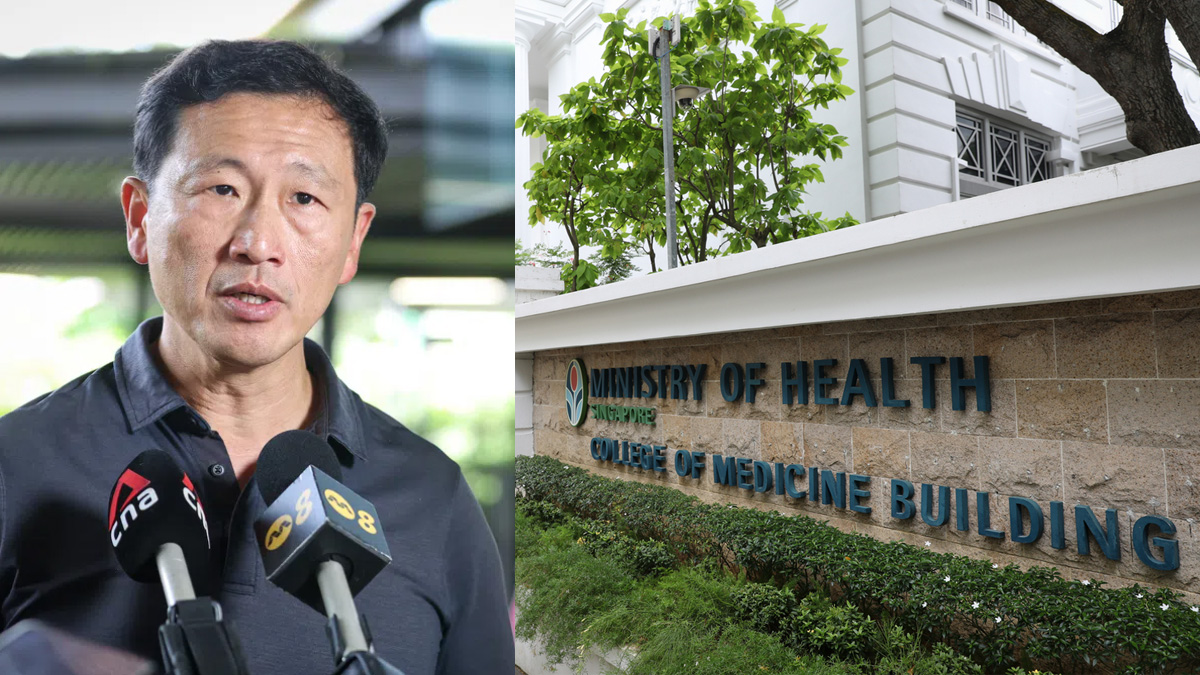

Ong Ye Kung: IP rider changes to rein in premiums and over-servicing

Health Minister Ong Ye Kung told Parliament new Integrated Shield Plan rider rules from 1 Apr 2026 will curb cost growth by ending deductible cover and raising co-payment caps, while keeping protection for major bills. He said MOH will watch for any shift to public hospitals and add surge capacity if needed.

- Ong Ye Kung said new IP rider rules aim to curb private healthcare inflation by restoring insurance to cover big, unexpected bills.

- MPs raised concerns over higher co-payments, protections for older policyholders, and whether insurers could erode coverage on existing riders.

- MOH will monitor any shift to public hospitals and may activate surge capacity for selected treatments if demand spikes.

Coordinating Minister for Social Policies and Minister for Health Ong Ye Kung told Parliament that new Integrated Shield Plan (IP) rider requirements are intended to restore insurance to its “original objective” of covering large, unexpected bills, amid concerns that generous riders have fuelled private healthcare inflation and rising premiums.

MPs raise concerns over affordability and ageing policyholders

In a Parliamentary question session on 12 January, MPs Mr Yip Hon Weng (Yio Chu Kang SMC), Ms Poh Li San (Sembawang West SMC) and Dr Hamid Razak (West Coast–Jurong West GRC) asked whether patients’ out-of-pocket costs would be capped, whether older rider policies could be retained, and what safeguards are in place to prevent insurers from indirectly reducing coverage for ageing policyholders.

In November last year, the Ministry of Health (MOH) announced new rules for Integrated Shield Plan (IP) riders with effect from 1 April 2026.

According to MOH’s press release issued on 26 November 2025, all new IP riders sold from that date must exclude coverage of the minimum deductible amount that policyholders are required to pay before insurance coverage begins.

MOH mandates minimum deductibles ranging from S$1,500 to S$3,500 depending on ward class. These must be paid once per policy year before any insurance payout applies.

At the same time, the current co-payment cap of S$3,000 will be doubled to S$6,000 per year for new riders.

This refers to the maximum sum a policyholder must pay out of pocket, beyond the deductible, for eligible claims—such as those involving pre-authorised procedures or panel doctors. The minimum 5% co-payment requirement will remain unchanged.

MOH said these changes aim to “bring health insurance back to its original objective, which is to protect patients against larger healthcare bills,” and to “increase cost discipline over minor episodes”.

Private hospital costs cited as key driver of system pressures

In his response on 12 January, Mr Ong said patient load has been shifting from private hospitals to public hospitals for more than a decade, driven by multiple factors, including preferences as people age.

But he singled out escalating private healthcare costs—“fuelled by” IP riders with overly comprehensive coverage—as a key contributor.

He cited a changing split in patient load between private and public hospitals, saying it moved from 15:85 in 2010 to 12:88 in 2020, and is now around 10:90.

Mr Ong argued that the rider issue is not the only driver, but said over-servicing and overconsumption are more likely when insurance covers nearly the entire bill.

Those higher bills, he said, translate into higher premiums.

Mr Ong told the House that private hospital IP rider premiums have been growing at about 17 per cent annually over the last three years, and that around 100,000 policyholders cancel or downgrade their IP rider policies each year—moves that can push more patients towards public hospitals.

Against that backdrop, Mr Ong said the new requirements will apply to riders purchased on or after 27 November 2025. For these affected riders, he said premiums “should be lower”, averaging about 30 per cent below current maximum-coverage rider designs.

The revised riders will also no longer cover the minimum deductible and will require higher co-payments, he added.

Mr Ong acknowledged MPs’ concerns about affordability for large bills, but said the policy is designed to preserve protection against “very large and unexpected” costs while removing coverage for the minimum deductible, which he suggested private-hospital users “tend to be able to afford”.

MediSave expected to cushion higher out-of-pocket payments

He outlined that the new rider design would still involve a 5% co-payment, capped at $6,000 a year in addition to deductibles.

He emphasised that this need not always be paid in cash because patients can use MediSave, and said MOH estimates that six in 10 rider claimants would not pay cash out of pocket after MediSave.

For the remainder, Mr Ong said the “majority” who pay cash out of pocket would pay $1,000 or less, and “practically all” would pay $3,000 or less.

He noted that the figures he cited were in the context of private hospital patients, whose premiums have risen sharply, and argued that premium savings under the new design could offset higher co-payments.

To illustrate, Mr Ong described a 60-year-old on a private hospital IP and maximum-coverage rider who could save about $1,600 a year in premiums by switching to the new rider—about $4,800 over three years—which he said would be enough to cover a typical higher co-payment, such as around $3,300 for a knee joint replacement in a private hospital.

Concerns over affordability and insurer repricing raised by MPs

Ms Poh asked how families facing hefty medical bills would be supported if co-payments became unaffordable.

Mr Ong replied that patients should consider both their financial circumstances and healthcare needs when deciding where to seek care, including subsidised treatment at public hospitals if affordability becomes an issue.

Mr Yip raised feedback from older residents worried that, even if existing riders can be kept, insurers might reprice or adjust benefits in ways that amount to de facto coverage reductions, leaving ageing policyholders with limited options.

Mr Ong responded that the “most important safeguard” is ensuring rider policies are sustainable, warning that “absolute peace of mind” coverage drives an “unsustainable” trajectory in which bills and premiums keep rising.

In follow-up exchanges, Ms Poh asked how the Government would prevent adverse selection, including the risk that those who cannot finance deductibles and co-payments might give up riders and delay treatment.

Without answering the question directly, Mr Ong stressed that Singaporeans retain access to subsidised public healthcare, describing this as the system’s underlying assurance, while noting that many existing rider holders are themselves reconsidering whether the premiums remain worth it.

Risk of greater strain on public hospitals debated

Dr Hamid said colleagues in restructured hospitals were concerned about already lengthening waiting times for subsidised patients, and feared a further surge if private rider holders switch to public care after April.

Mr Ong said he was “equally concerned”, but argued that the rider changes are necessary to tackle a root cause of the private-to-public shift and to keep private healthcare accessible in the long term.

He added that MOH is already expanding capacity—both hospital beds and outpatient services—to meet the needs of an ageing population. In the short term, he said MOH will monitor the shift closely, and, “if need be”, may implement surge capacity for selected treatments.

Questions then turned to oversight of insurer behaviour as part of the wider health system.

Oversight of insurers questioned as MOH defends regulatory levers and market balance

Mr Kenneth Tiong, MP for Aljunied GRC, asked what enforcement levers MOH has to ensure insurer conduct advances healthcare affordability and access, given that the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) is primarily the financial regulator.

He also asked whether accountability for insurers as “health system actors” is a gap that needs to be addressed.

Mr Ong replied that the rider framework itself had become a problem and MOH was acting on it, describing this as proof that the Government would intervene when arrangements are not sustainable or not in patients’ interests.

He said MOH and MAS have “plenty of levers” and will work together to ensure insurers operate ethically, remain viable, and serve patients’ interests.

He added that MOH’s responsibility is to run the public healthcare system to ensure universal accessibility, while allowing private healthcare to operate through market dynamics.

But he said where markets do not operate fairly, the Government will regulate—setting key parameters to ensure clinical effectiveness and safety, and to keep the system sustainable without “serious market failure”.

Balancing regulation with market dynamics in private healthcare

At the same time, Mr Ong cautioned against micromanaging private-sector conduct, arguing it would be contradictory to claim to leave matters to the market while controlling every action.

If Singapore wanted full control, he said, it would amount to nationalisation—and the country already has a large, nationalised public healthcare system. For private healthcare, he said the approach should be to regulate the essentials and let the market operate.

Later, Mr Fadli Fawzi, MP for Aljunied GRC, asked whether there is sufficient surge capacity to cope if more private patients move into the public system after the policy change, particularly for smaller procedures that fall under the deductible threshold.

Mr Ong said the shift from private to public care is a “secular trend” that has been unfolding for the past 15 to 20 years, and is driven mainly by rising demand from an ageing population.

He said MOH will continue a multi-pronged approach—expanding capacity, keeping people healthier and moderating demand, especially by reducing unnecessary treatment and wastage.