Amnesty urges Indonesia to halt bill on disinformation and foreign propaganda

Amnesty International has called on Indonesia to stop plans for a Bill on Countering Disinformation and Foreign Propaganda, warning it could be used to suppress free expression and silence critics under the guise of national security.

- Amnesty International has urged Indonesia to halt plans for a Bill on Countering Disinformation and Foreign Propaganda, citing risks to freedom of expression.

- The group warns the bill could allow the state to define “truth” and suppress criticism under the banner of national security.

- Despite concerns, the government and parliament have expressed support for drafting the legislation in 2026.

Amnesty International has urged the Indonesian government to immediately halt plans to draft a Bill on Countering Disinformation and Foreign Propaganda, warning that the proposal risks becoming a new legal instrument to suppress freedom of expression rather than a genuine safeguard against information threats.

The warning follows the circulation of an official Academic Paper by the Ministry of Law, which recommends that the bill be drafted without delay and included in the 2026 Priority National Legislation Programme (Prolegnas) of the House of Representatives of Indonesia.

The government has framed the initiative as a response to alleged information attacks and propaganda by foreign actors said to be undermining Indonesia’s national interests. Human rights groups, however, argue that the proposal lacks urgency, is conceptually flawed, and poses a serious threat to constitutional rights.

‘A Dangerous Expansion of State Power’

The Executive Director of Amnesty International Indonesia, Usman Hamid, said the bill would likely add to what he described as Indonesia’s growing list of laws that are frequently used to criminalise dissent.

“The government’s plan to draft a Bill on Countering Disinformation and Foreign Propaganda is a move whose urgency must be questioned,” Usman said. He warned that the proposal carries a high risk of violating Article 28E of Indonesia’s 1945 Constitution, which guarantees freedom of expression, as well as Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

According to Amnesty, the most serious concern lies in how “foreign propaganda” would be defined and who would have the authority to determine it. “Granting the state the power to decide which information is true and which constitutes foreign propaganda effectively positions the government as the sole arbiter of truth,” Usman said.

Accusations of State-Backed Disinformation

Amnesty also criticised what it described as a pattern of unsubstantiated accusations by state officials, including the President, linking civil society criticism to unnamed foreign interests. Such narratives, Usman argued, amount to a form of state-backed disinformation.

“If criticism is repeatedly associated with foreign forces without evidence, then it is the government itself that is spreading disinformation,” he said, warning that a new law would legitimise this practice and embed it in the legal system.

Background: How the Bill Emerged

The proposal for the bill must be understood within a broader political and regulatory context. The 67-page Academic Paper issued by the Ministry of Law argues that Indonesia lacks an integrated legal framework to counter disinformation and foreign propaganda that could threaten national unity, democratic processes, and information sovereignty.

The document situates the proposal within a global narrative of “information warfare”, citing the increasing use of social media, artificial intelligence, and transnational digital networks to influence public opinion and destabilise states. It recommends swift legislative action to provide legal certainty for prevention, detection, and mitigation efforts.

This framing aligns Indonesia with a growing number of governments worldwide that have adopted or proposed laws to counter foreign influence operations. However, critics note that such legislation has often been controversial, granting wide discretionary powers to the executive while offering limited safeguards for civil liberties.

Political momentum behind the bill intensified on 14 January 2026, when Coordinating Minister for Legal Affairs, Human Rights, Immigration, and Corrections Yusril Ihza Mahendra said that Prabowo Subianto had instructed the drafting of the legislation to counter information attacks by foreign parties deemed harmful to national interests.

Support has also emerged from parliament. On 16 January, Sukamta, Deputy Chair of Commission I of the DPR — which oversees defence, foreign affairs, and communications — welcomed the initiative, describing disinformation in Indonesia’s digital space as increasingly “massive and systemic”. With the DPR dominated by parties aligned with the governing coalition, civil society groups fear the bill could advance rapidly with limited public consultation.

A Pattern of Restrictive Digital Laws

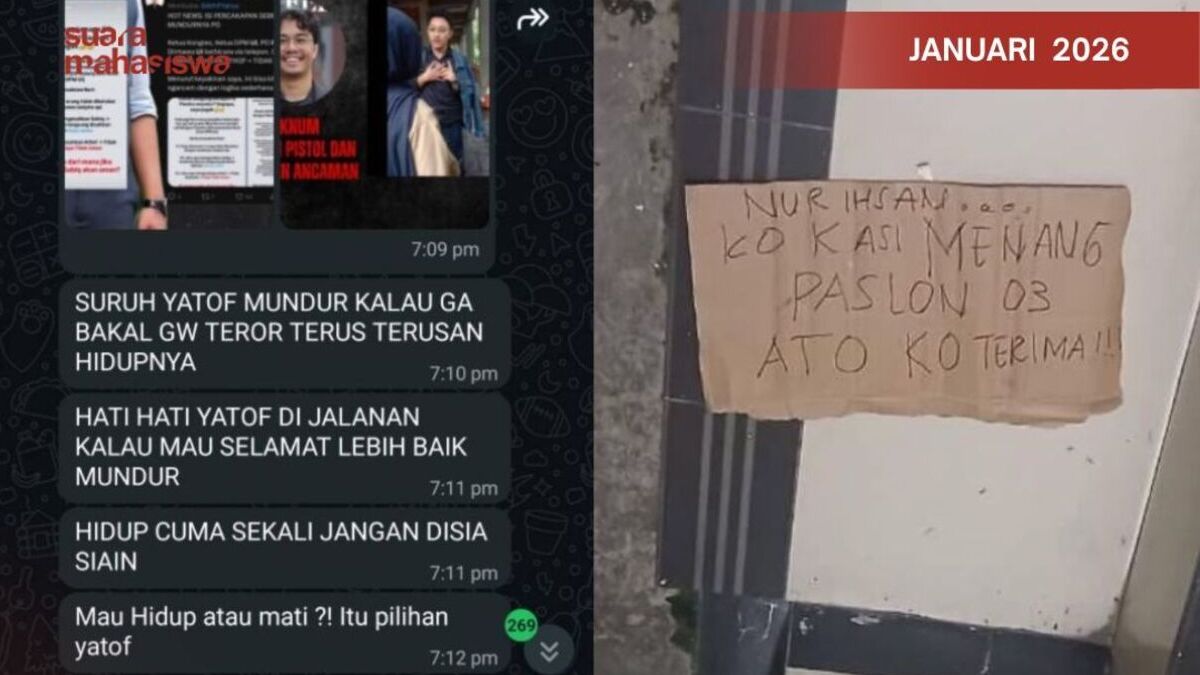

Human rights organisations argue that the proposed bill cannot be separated from Indonesia’s recent legislative history. Existing regulations, particularly provisions in the Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law, have been widely criticised for being used to prosecute journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens for online expression.

Against this backdrop, Amnesty argues that the new bill represents not a necessary innovation, but a continuation of a regulatory approach that prioritises control over rights. Without clear definitions, strict limitations, and independent oversight, the concept of “foreign propaganda” could easily be expanded to encompass domestic dissent, advocacy, or investigative journalism.

Political Contradictions and Weak Urgency

Amnesty also points to what it calls a contradiction in government policy. While officials warn of foreign threats to sovereignty, the administration has simultaneously pursued aggressive foreign investment and international partnerships, including calls for foreign universities to establish campuses in Indonesia.

“This inconsistency raises serious doubts about whether the bill is genuinely about national security,” Usman said. “It appears instead to reflect an attempt to legalise suspicion towards public criticism.”

Calls to Halt the Drafting Process

Amnesty concluded that the bill lacks genuine urgency and risks becoming a new instrument to silence human rights defenders and critical civil society voices. Rather than strengthening Indonesia’s resilience, the organisation warned, it could undermine democratic accountability.

“In order to safeguard freedom of expression,” Usman said, “the plan to draft this bill must be halted immediately.”

As debate over the proposal continues, the bill is emerging as a key test of Indonesia’s commitment to democratic fr eedoms in an era of heightened concern over disinformation and digital influence.