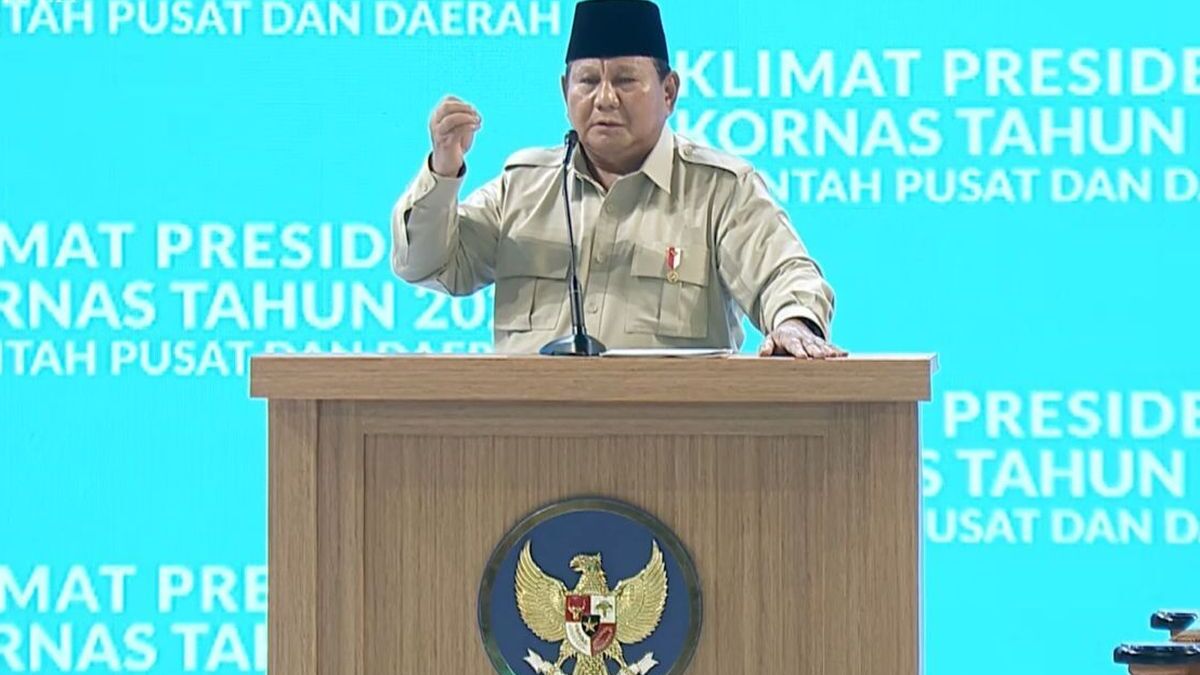

Indonesia’s CPI ranking falls as watchdog cites governance failures under Prabowo administration

Indonesia Corruption Watch says systemic governance failures under President Prabowo Subianto have driven a sharp fall in Indonesia’s 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index ranking, warning that decades of anti-corruption reforms are being eroded.

- Indonesia fell ten places in the 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index, prompting sharp criticism from Indonesia Corruption Watch.

- ICW attributes the decline to weakened enforcement, stalled legislative reforms and growing conflicts of interest within state institutions.

- The group warns that decades of post-1998 anti-corruption reforms risk being eroded without structural changes.

Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) has attributed Indonesia’s worsening standing in the global Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) to what it describes as systemic governance failures under President Prabowo Subianto’s administration, warning that anti-corruption reforms built over nearly three decades are being steadily eroded.

In a statement issued on 10 February 2026, the civil society watchdog said the government’s approach over the past year has fostered an environment in which conflicts of interest, nepotism and patronage networks have become normalised within state institutions, weakening law enforcement and undermining public trust.

The criticism follows Indonesia’s significant drop in the 2025 CPI rankings, a decline ICW describes as a warning sign that anti-corruption commitments remain largely rhetorical rather than substantive.

Sharp decline signals weak enforcement

ICW noted that Indonesia fell by ten places within a single year, reflecting what it sees as ineffective enforcement measures and the absence of a credible deterrent against corruption.

One component contributing to the CPI score, the IMD Business School World Competitiveness Yearbook, recorded a steep fall in Indonesia’s performance on indicators measuring the prevalence of bribery and corruption.

The country’s score reportedly dropped from 45 to 26 points, suggesting worsening perceptions among business actors regarding corruption risks.

According to ICW, this decline reflects the administration’s failure to implement meaningful reforms or strengthen institutions responsible for combating corruption.

The organisation also criticised both the government and the House of Representatives (DPR) for failing to prioritise legislative measures needed to strengthen anti-corruption frameworks.

Key proposals remain stalled, including efforts to restore the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) Law to its pre-2019 provisions, when the body operated with greater independence.

Similarly, progress has stalled on deliberations over the Asset Confiscation Bill, as well as revisions to anti-corruption legislation intended to align Indonesia’s laws with commitments under the United Nations Convention Against Corruption.

These include provisions criminalising influence peddling and corruption in private sector transactions.

Without these reforms, ICW argues, enforcement agencies remain structurally weakened.

Prevention mechanisms also deteriorating

Beyond enforcement failures, ICW also highlighted declining corruption prevention efforts, citing assessments from the Bertelsmann Stiftung Transformation Index.

Effective prevention, the group argues, depends on managing conflicts of interest within state institutions. Instead, the current political environment has allowed such conflicts to flourish.

ICW pointed to what it described as the allocation of strategic government and economic positions to political allies, family members and figures connected to the president’s inner circle.

The expansion of the cabinet and the appointment of deputy ministers who simultaneously hold positions as commissioners in state-owned and private enterprises were cited as examples of overlapping interests.

Concerns were also raised regarding governance arrangements surrounding the Free Nutritious Meals programme, where foundations overseeing the initiative reportedly include individuals linked to political parties, law enforcement institutions and military circles.

More recently, the appointment of a presidential relative as Deputy Governor of Bank Indonesia has drawn criticism from governance observers, who warn that such decisions risk undermining the central bank’s independence.

ICW argues that corruption prevention can only function effectively if parliament maintains its constitutional role as a check on executive authority.

However, with an overwhelming majority of parliamentary seats now held by parties aligned with the governing coalition, the DPR is seen as increasingly reluctant to challenge executive policies.

As a result, ICW claims, parliament has shifted from acting as a counterbalance to becoming a facilitator of executive initiatives that often favour elite political interests.

Law enforcement and judicial independence under scrutiny

ICW also linked the CPI decline to deteriorating conditions within Indonesia’s legal system and weakened access to justice.

The organisation criticised the government’s reliance on salary increases for judges and law enforcement officials as a solution to entrenched corruption within the judiciary. While improved remuneration may help, ICW argues that deeper structural reforms are required to dismantle so-called “judicial mafia” networks that allegedly manipulate legal outcomes.

The group further expressed concern over executive interference in judicial processes, including the use of presidential powers such as amnesty, abolition or rehabilitation measures to overturn or mitigate court verdicts in corruption cases.

Such practices, according to ICW, undermine judicial independence and erode confidence in the rule of law.

Public participation under pressure

ICW also emphasised the importance of public oversight in uncovering corruption cases, noting that many investigations originate from whistle-blowers or civil society reporting.

However, throughout 2025, individuals participating in anti-corruption efforts reportedly continued to face intimidation, legal counter-attacks or retaliation, discouraging public engagement.

If the government genuinely seeks to strengthen corruption law enforcement, ICW argues, protection for whistle-blowers and public participation must become a core policy commitment rather than an afterthought.

Reform momentum at risk

Indonesia’s anti-corruption reforms, initiated after the fall of authoritarian rule in 1998, were once seen as a cornerstone of democratic consolidation. Institutions such as the KPK emerged as symbols of reform and public accountability.

ICW now warns that these gains are increasingly under threat, with weakening institutions and growing political consolidation undermining decades of reform progress.

The watchdog concludes that without decisive structural action — including strengthening institutional independence, restoring legislative reforms and protecting public oversight — Indonesia risks further erosion of governance standards.