Prabowo defends palm oil expansion, calls oil palm a “miracle crop”

President Prabowo Subianto has defended the expansion of Indonesia’s palm oil industry, calling oil palm a “miracle crop” essential for energy independence and economic strength, while dismissing critics of plantation growth.

- President Prabowo Subianto defended further palm oil expansion, calling oil palm a “miracle crop” vital for energy independence.

- He argued palm-based biofuels could reduce fuel imports and strengthen Indonesia’s global commodity position.

- Environmental and social concerns remain as plantation growth continues to face scrutiny.

Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto has defended the expansion of the country’s palm oil industry, describing oil palm as a “miracle crop” capable of securing national energy independence and strengthening Indonesia’s position in global commodity markets, while dismissing critics who oppose further plantation growth.

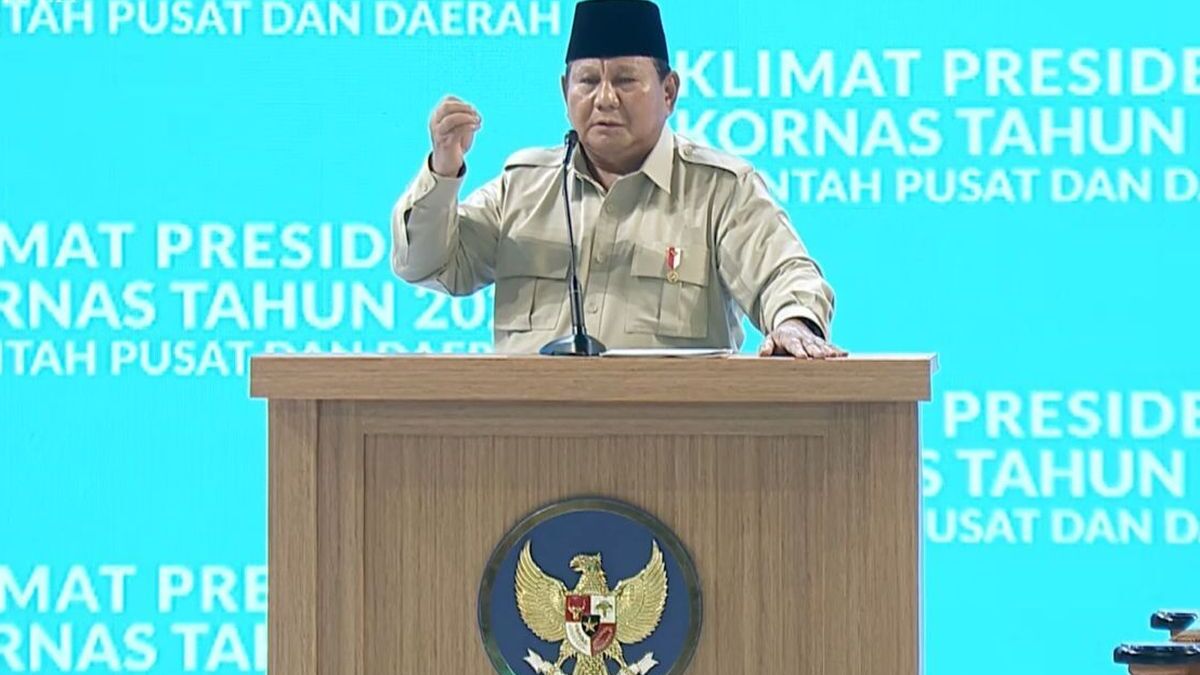

Speaking before thousands of central and regional officials at the 2026 National Coordination Meeting of Central and Regional Governments at the Sentul International Convention Center (SICC) near Jakarta on Monday, 2 February, Prabowo portrayed palm oil as a strategic asset central to Indonesia’s economic and energy future.

The meeting, attended by ministers, governors, regents, mayors and senior bureaucrats, focused on aligning national and regional policy priorities under Prabowo’s administration, particularly in areas of food and energy self-sufficiency.

Palm Oil as a Strategic Commodity

In his address, Prabowo argued that oil palm cultivation provides Indonesia with unique economic and industrial advantages unmatched by other crops.

“Why do I call oil palm a miracle crop? It is a miracle crop,” he told participants. “Some people complain and ask why oil palm. They say Prabowo wants to expand oil palm. Yes — for the Indonesian people.”

He stressed that palm oil should not be viewed solely as cooking oil, noting its wide use in manufacturing and consumer products across the world.

According to the president, palm oil derivatives are used in products ranging from food ingredients and cosmetics to detergents, paints and industrial materials.

“Wall paint needs palm oil. Food products and bread use palm oil. Soap is used daily by billions of people around the world,” he said, joking that only “those reluctant to bathe” might avoid products containing palm derivatives.

Indonesia is already the world’s largest producer and exporter of palm oil, with plantations covering more than 16 million hectares across Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Papua. The commodity remains one of the country’s most valuable export earners, generating billions of dollars annually and supporting millions of jobs, from plantation labourers to refinery and logistics workers.

Energy Independence Through Biofuel

Prabowo framed palm oil not merely as an export commodity but as a cornerstone of Indonesia’s ambition to reduce dependence on imported fuel.

Indonesia has long been a net importer of petroleum products despite being an oil producer, creating pressure on state finances due to fuel subsidies and import costs.

The president argued that palm oil-based biofuels could help eliminate this dependency.

“More importantly, oil palm can be turned into diesel fuel,” he said. “Biodiesel and bio-solar will free us from dependence on foreign supply.”

Indonesia already operates one of the world’s largest biodiesel blending programmes. The government plans to increase mandatory biodiesel blending levels to B50 — meaning fuel contains 50 per cent palm-based biodiesel — later this year.

Officials expect the programme to cut diesel imports, stabilise domestic fuel supplies and provide cheaper energy options for consumers.

Prabowo also suggested biofuel could serve as a lower-cost alternative for ordinary Indonesians.

“Those who want to use petrol can continue using it and pay global prices. But our people can rely on diesel,” he said.

Beyond road transport, he claimed palm oil could be used to produce aviation fuel, predicting Indonesia could become the world’s largest supplier.

He added that even palm oil waste and used cooking oil could be converted into aviation fuel, and signalled plans to restrict exports of such waste products so they can instead be processed domestically.

“I apologise to other nations, but we will close and ban exports of palm oil waste and used cooking oil. It must serve Indonesia’s interests first,” Prabowo said.

Strong Global Demand

The president also emphasised strong international demand for Indonesian crude palm oil (CPO), saying foreign leaders frequently raise the issue during bilateral meetings.

“I travel around the world, and almost every leader asks Indonesia for assistance in supplying palm oil,” he said, citing visits to Egypt, Pakistan, Russia and Belarus.

“That shows palm oil is a very strategic commodity.”

Indonesia supplies palm oil to markets across Asia, Africa and Europe, where it is widely used in food manufacturing and industrial products. However, exports have also faced regulatory and environmental scrutiny, particularly in the European Union, where new rules aim to limit imports linked to deforestation.

Domestic Policy Context

Prabowo’s remarks reflect a broader national strategy emphasising self-sufficiency in food and energy, themes repeatedly highlighted since he assumed office.

The government is simultaneously pushing major programmes to expand domestic food production, develop biofuel industries and strengthen rural economies.

During the same coordination meeting, Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto also discussed government plans to support domestic industries through state-funded projects, including an initiative to revitalise Indonesia’s roofing industry by encouraging the use of locally produced clay tiles rather than imported or less durable metal roofing.

Officials argue that such programmes can stimulate local manufacturing, improve housing conditions and enhance tourism appeal.

Environmental and Social Concerns

Despite government optimism, palm oil expansion remains one of the most contentious issues in Indonesia’s development policy.

Environmental groups warn that plantation expansion has historically contributed to deforestation, biodiversity loss and peatland degradation, increasing greenhouse gas emissions and worsening flood and fire risks.

Human rights organisations have also documented conflicts between companies and Indigenous communities over land rights, particularly in frontier regions such as Papua, where new plantation development is under discussion as part of national strategic projects.

Critics argue that plantation expansion often occurs without adequate consultation or compensation for local communities and may threaten customary forest lands that sustain Indigenous livelihoods.

Government officials maintain that new development must follow legal and environmental safeguards, though activists question whether enforcement is strong enough to prevent abuses.