Civicus Monitor warns Singapore’s new online safety bill risks deepening censorship of free expression

Civicus Monitor has cautioned that Singapore’s new Online Safety (Relief and Accountability) Bill may become another instrument for the government to restrict free speech. Critics say its broad provisions could be used to silence dissent, expanding on laws such as POFMA and FICA that already constrain civic freedoms.

- Civicus Monitor warns that Singapore’s new Online Safety (Relief and Accountability) Bill may further curtail free expression.

- The government claims it aims to protect users from online harm, but critics say it will tighten censorship.

- Rights groups argue the bill expands ministerial powers, mirroring earlier restrictive laws like POFMA and FICA.

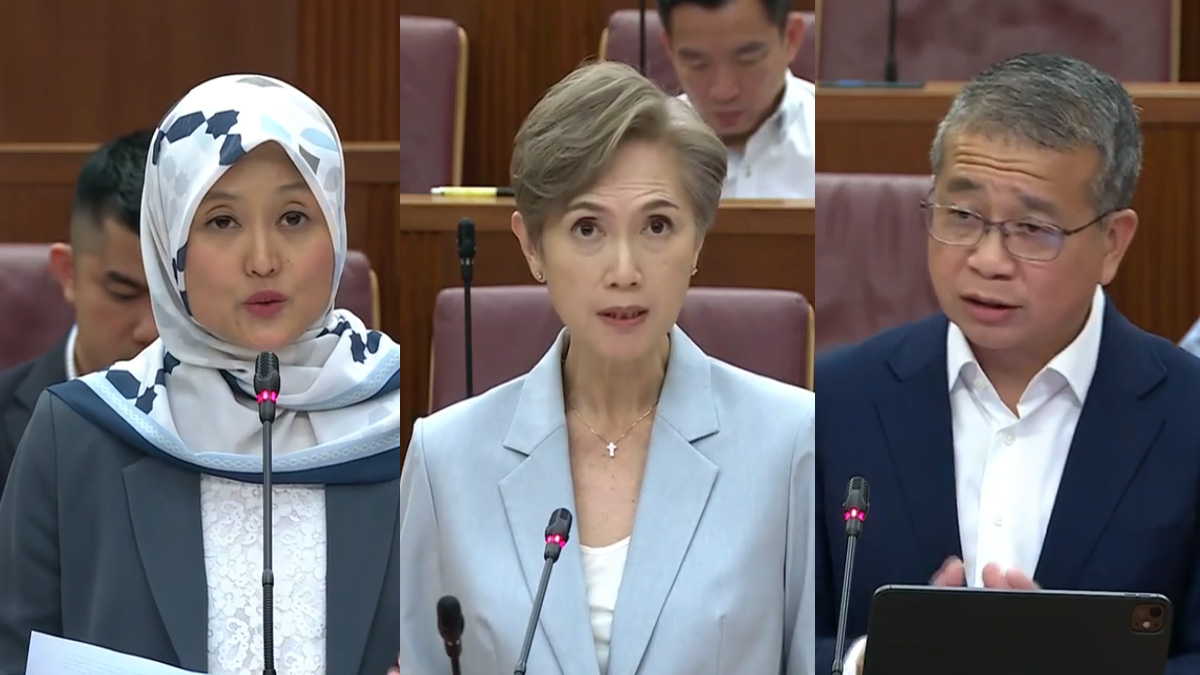

Civicus Monitor has raised concerns about Singapore’s proposed Online Safety (Relief and Accountability) Bill (OSRA), which is set for debate in Parliament next week and is widely expected to pass.

The organisation, a global civil society alliance that advocates for participatory democracy and freedom of association, described the move as part of a broader pattern of shrinking civic space in Singapore.

Critics warn of ‘weaponisation’ of law

Josef Benedict, Civicus Monitor’s Asia-Pacific representative, told California-based independent media outlet Asia Sentinel on 27 October 2025 that the OSRA Bill is just the "latest move by the Singaporean government to weaponise the law to impose even more stringent online restrictions on freedom of expression.”

Benedict said that while the government argues the law aims to protect individuals from online harm, “there is a genuine fear that the vague and broad provisions in the law will be used to silence peaceful government critics.”

He cited earlier legislation such as the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) and the Foreign Interference (Counter-Measures) Act (FICA) as examples of laws “passed under the guise of national security or combating misinformation but misused to censor critical news, and to target activists, journalists, and opposition politicians.”

International rights bodies urge reform

Benedict added that instead of passing “another draconian law,” Singapore’s government should act on recommendations by the UN Human Rights Council, which has urged the review or repeal of restrictive laws, the ratification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the establishment of an independent national human rights commission.

Civicus Monitor currently rates Singapore’s civic space as “repressed”, citing the systematic use of restrictive legislation to criminalise critics, suppress dissenting activities, and impose tight constraints on peaceful assembly.

New law expands scope of online regulation

The proposed OSRA is expected to take effect after parliamentary approval, adding to existing controls over online expression. It builds upon POFMA—passed in 2019 and commonly known as the “Fake News” law—by granting authorities broader powers to act against what they define as online harms.

According to the bill, an Online Safety Commission (OSC) would be established by June 2026 as a “one-stop” body to regulate 13 categories of online harms.

These include harassment, doxxing, stalking, intimate image abuse, and child exploitation. Individuals found guilty could face fines up to S$20,000 (US$15,395) or imprisonment of up to 12 months. Platforms and data-hosting sites could face penalties as high as S$500,000.

Public support cited for the new law

The Ministry of Digital Development and Information (MDDI) said the bill responds to findings from national surveys conducted between November 2024 and May 2025, involving over 2,000 residents.

More than 80 percent reported encountering harmful online content, and about two-thirds supported stronger online safety rules even if they curtailed some user freedoms.

Officials argue that the bill is designed to address real harm and protect vulnerable users from abuse.

Concerns over vague definitions and political control

However, critics warn that the expanded mandate of the OSC could open the door to political censorship.

The Straits Times reported that the OSC’s scope would gradually widen to cover offences such as online impersonation, deepfake abuse, incitement of violence, and “publication of false or reputationally harmful statements.”

Observers note that such broad phrasing could allow authorities to categorise legitimate investigative journalism or critical commentary as “reputational harm.”

Examples from past incidents reinforce these concerns.

In 2024, The Online Citizen reported on a minister’s S$88 million property sale, sparking the issuance of POFMA correction directions and a defamation dispute, following a report by Bloomberg and others on the transactions involving the minister and another minister.

Similarly, social media user Rich Sng faced scrutiny for posts showing ministers with a convicted money launderer—content that might have been punished under the OSRA’s proposed definitions.

Oversight concentrated under ministerial authority

The bill also gives substantial discretionary powers to the MDDI minister.

The OSC commissioner and its Appeal Committee would be appointed by Josephine Teo, who has led the ministry since April 2021.

Critics argue this structure undermines the independence of oversight mechanisms and entrenches ministerial interpretation over what constitutes “false” or “reputationally harmful” material.

This follows a precedent set in a 2021 Court of Appeal ruling in The Online Citizen’s POFMA appeal, where the court upheld that challenges could only question whether a statement was false according to the minister’s interpretation, not based on public reasonableness or accuracy.

Rights groups draw parallels with FICA and POFMA

Human Rights Watch, in its 2025 World Report, said Singaporean authorities “frequently use overly broad and restrictive laws to silence criticism of the government and restrict freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.”

The report highlighted both POFMA and the Hostile Information Campaigns provisions of FICA, which allow the Home Affairs Minister to order the removal of online content, publish mandatory government messages, ban applications, or compel social media platforms to hand over user data.

The OSRA, critics argue, continues this pattern—consolidating administrative control while presenting its measures as public safety initiatives.