Indonesia’s free nutritious meals programme dominates 2026 budget, raising fiscal concerns

Indonesia’s Rp 335 trillion Free Nutritious Meals programme dominates the 2026 budget, prompting debate over fiscal discipline, weak targeting, and whether scarce public funds are reaching the most vulnerable communities.

- Indonesia has allocated Rp 335 trillion to its Free Nutritious Meals programme in the 2026 Draft State Budget, making it one of the largest spending items nationwide.

- Critics argue the programme is poorly targeted, fiscally risky, and diverts resources from education quality and poverty-focused interventions.

- The concentration of benefits in relatively wealthy regions raises questions about whether the policy addresses undernutrition where it is most severe.

The controversy surrounding Indonesia’s Free Nutritious Meals programme (Makan Bergizi Gratis, MBG) has gone viral across the country in recent weeks, sparking intense public debate on social media, in newsrooms, and among policy analysts.

The renewed scrutiny has been driven in part by public frustration that the programme continued to operate and draw heavily on state funds even while schools across Indonesia were closed for the year-end holidays for nearly three weeks, from mid-December until early January.

Many citizens have questioned the logic and urgency of sustaining a costly school-based programme during a period when students were largely absent, especially as other pressing crises demanded attention.

This surge of criticism has come despite the fact that the programme’s massive budget was formally approved by the House of Representatives as part of the 2026 Draft State Budget in September last year, with little public scrutiny at the time.

The backlash has been further fuelled by public demands for the government to prioritise flood recovery efforts in Sumatra, where rehabilitation and aid distribution have been widely perceived as slow and inadequate following devastating floods and landslides.

Together, these factors have intensified concerns about policy priorities, fiscal discipline, and the government’s responsiveness to urgent humanitarian needs.

Indonesia’s 2026 Draft State Budget (RAPBN), approved by the House of Representatives in September 2025, places the Free Nutritious Meals programme (Makan Bergizi Gratis, MBG) at the centre of fiscal policy.

With an allocation of Rp 335 trillion (approximately US$21.3 billion), MBG has become one of the single largest spending items in the State Budget—larger than many entire ministerial budgets and dwarfing other social and human capital programmes.

For foreign observers, the scale, structure, and implementation of MBG raise fundamental questions about fiscal discipline, policy priorities, and whether public funds are being directed to those most in need.

An Exceptionally Large Allocation by Any Measure

At Rp 335 trillion (approximately US$21.3 billion), the MBG budget is extraordinary in comparative terms. It represents a dramatic increase from approximately Rp 71 trillion (about US$4.5 billion) the previous year and absorbs an outsized share of the national education budget.

Of the Rp 769.1 trillion (US$49.0 billion) allocated to education in 2026, Rp 223 trillion (approximately US$14.2 billion)—nearly 30 per cent—is channelled into MBG alone.

This scale becomes even more striking when set against other priorities. Scholarship programmes for school and university students receive just Rp 57.7 trillion (around US$3.7 billion), while funding for non-civil servant teachers, regional civil servants, and lecturers stands at Rp 91.4 trillion (approximately US$5.8 billion).

In effect, a programme providing one meal per day now consumes far more public money than direct investments in teaching staff, educational quality, or student financial aid.

From a budgetary perspective, MBG is not merely large; it is dominant. Few social assistance programmes anywhere in the region command such a proportion of national expenditure, particularly for a benefit that is universal rather than targeted.

Where the Money Comes From—and Where It Goes

The MBG budget is financed through a complex reallocation across sectors. According to official government data, 83.4 per cent of its funding comes from the education sector, with the remainder drawn from health (9.2 per cent) and economic programmes (7.4 per cent).

This blending of mandates blurs accountability and makes it harder to assess whether the programme is achieving outcomes in any one sector.

On the spending side, nearly all funds—around Rp 261 trillion (US$16.6 billion), or 97.7 per cent—are classified as goods expenditure, primarily for food procurement.

Personnel costs and capital spending together account for less than 3 per cent. Such a structure leaves little room for long-term capacity building, nutrition education, or improvements in health and sanitation that might deliver more durable benefits.

Senior officials at the National Nutrition Agency (BGN), which manages MBG, have acknowledged ongoing budget absorption problems.

Even as the agency admits that Rp 9.1 trillion (round US$580 million) remains unused, it is simultaneously projecting the need for an additional Rp 50 trillion (approximately US$3.2 billion) and relying on Rp 100 trillion (about US$6.4 billion) in standby funds set aside by the President.

For critics, this combination—underutilised funds alongside demands for more money—underscores concerns about planning and execution.

Fiscal Risk and Opportunity Costs

Indonesia’s Finance Minister has publicly warned about large allocations that fail to translate into timely public benefits, signalling the possibility of reallocating underused funds.

In the case of MBG, the risk is not only inefficiency but opportunity cost. Every rupiah committed to a universal meal programme is a rupiah not spent on infrastructure, targeted poverty alleviation, healthcare access, or improving the quality of schools and universities.

Economist Lili Yan Ing has argued that, based on population data, MBG should cost no more than Rp 8 trillion (approx. US$471 million).

Students make up roughly 4 per cent of Indonesia’s population, and the programme provides only lunch. By this reasoning, the current allocation is not merely generous but excessive by an order of magnitude.

The gap between Rp 8 trillion (about US$0.5 billion) and Rp 335 trillion (US$21.3 billion) represents a vast pool of resources that could otherwise be deployed for more productive investments.

A Programme Poorly Targeted

Beyond its cost, MBG faces mounting criticism for weak targeting. Data from Indonesia’s National Socio-Economic Survey show that only around 7 per cent of students are undernourished.

This means that the vast majority of beneficiaries already meet their daily nutritional needs. In such cases, free meals do little to improve health outcomes and may instead generate food waste or, as reported in some areas, even food safety incidents.

Macroeconomic analysts warn that the programme’s economic impact depends entirely on whether it increases consumption among genuinely undernourished groups—such as children who previously ate only once a day. Where this condition is not met, MBG risks becoming an expensive transfer with minimal social return.

Mismatch with Regional Poverty Patterns

Perhaps the most serious criticism concerns where MBG is being rolled out.

Indonesia’s poverty is highly uneven. Provinces in Papua and eastern Indonesia record poverty rates exceeding 20 per cent, with rural poverty in some areas approaching 40 per cent. By contrast, provinces such as Bali, Jakarta, and parts of Kalimantan have poverty rates below 5 per cent.

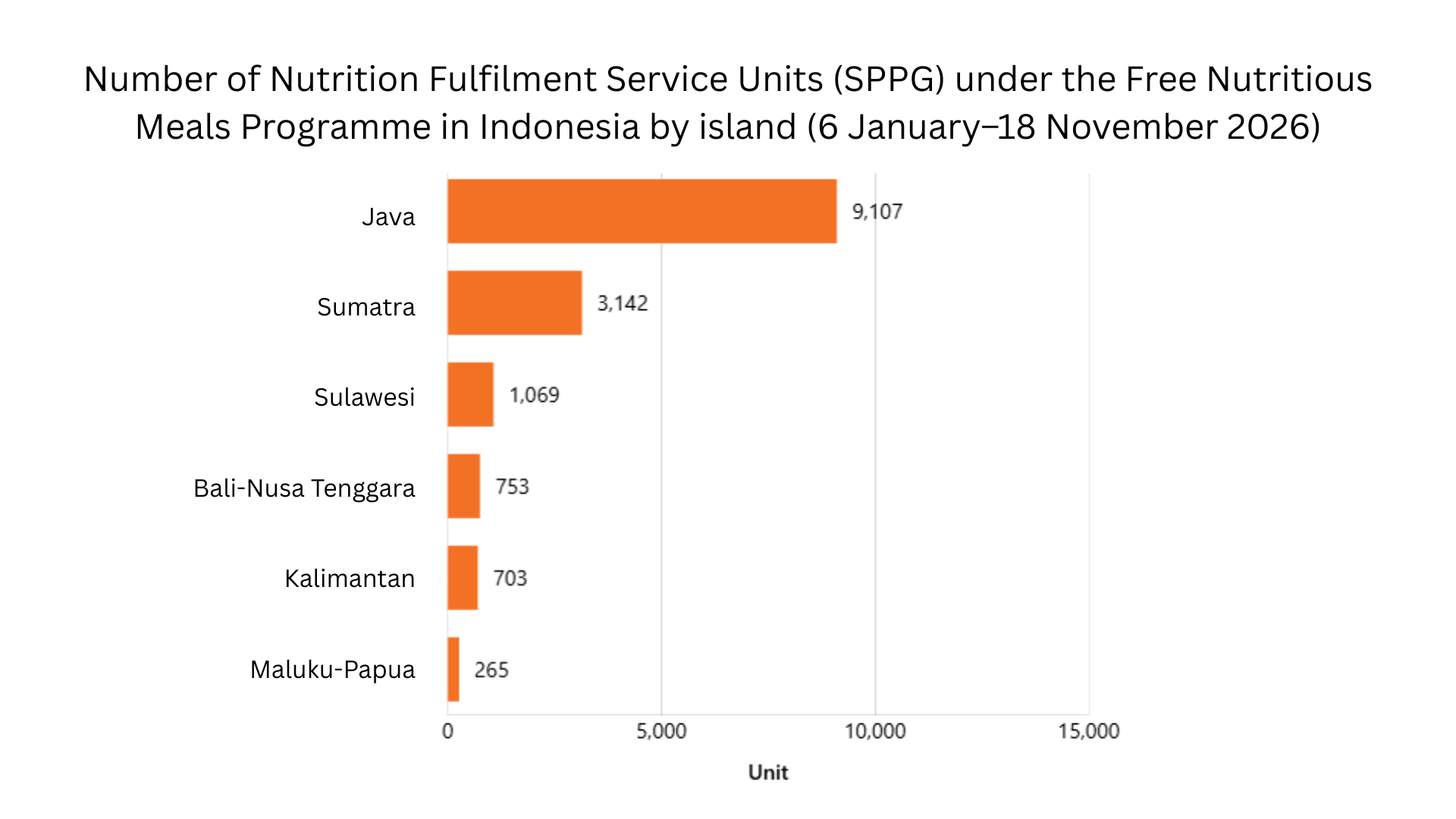

Yet the distribution of Nutrition Fulfilment Service Units (SPPG), as reflected in official data and illustrated in the accompanying material, shows that MBG facilities are heavily concentrated in relatively prosperous regions, particularly on Java.

These are areas where most students already consume three meals a day and where poverty is comparatively low. Meanwhile, remote rural areas in Papua, Maluku, and eastern Indonesia—where undernutrition is more prevalent and logistical challenges are greatest—remain underserved.

This mismatch undermines the programme’s stated objectives.

A universal approach may be administratively simpler, but in a country as geographically and socio-economically diverse as Indonesia, it leads to substantial leakage to non-poor households while failing to prioritise those facing the most acute deprivation.

Economic Stimulus or Costly Symbolism?

The government argues that MBG will stimulate economic growth, create up to three million jobs, and inject liquidity into local economies through advance payments to service providers.

While such multiplier effects are plausible, they are not guaranteed.

If procurement is inefficient, supply chains are poorly managed, or meals are delivered where they are not needed, the stimulus effect may fall far short of projections.